Homes in Indian Country are three times more likely to be crowded than those in the United States as a whole, according to the 2010 Census. Many of the people sleeping on sofas or floors in these crowded dwellings are homeless – not living outdoors or in a car, but not living in permanent homes of their own, either. Strong kinship networks often enable people to find a place to stay and there are few shelters and service providers in places with small, spread-out populations.

As a result, data documenting the need for homelessness assistance on American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian lands is scarce, and too often the assistance does not reach those who need it. The obvious challenges of collecting data in sparsely populated areas are further complicated by a lack of understanding of tribal sovereignty, a lack of familiarity with distinct Indian nations, and a lack of cultural awareness on the part of those outside the tribe. In addition, many tribal households are reticent about participating in surveys, typically as a result of being over-studied in the past. This is especially true for surveys conducted by non-native interviewers that do not clearly result in tangible benefits for native communities. Other concerns include difficulty in effective communication due to cultural and, in many cases, language differences.

Congress and HUD have taken one important step towards addressing homelessness in Native American and rural areas: they broadened the definition of homelessness beyond literal homelessness, the condition of living on the street or in a shelter. The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act (HEARTH) of 2009 and regulations issued by HUD in December 2011 recognize that people living doubled-up in a place where they cannot stay indefinitely are also homeless.

These individuals are not, however, included in the Point-in-Time counts conducted by Continuums of Care. (CoCs are entities that plan for and provide HUD-funded homelessness services within an identified geographic area such as a city, a county, or a metropolitan area. In most states, a single “balance of state” CoC covers small cities and rural areas that are not included within other CoCs.) The PIT counts enumerate people in shelters and those who are unsheltered. They may not find Native Americans living unsheltered in remote rural places, and they cannot identify those who live doubled-up.

Collection of better data, then, must be conducted locally. To obtain accurate results, there is a strong need for trust between the community and those conducting a homeless survey. Cultural competency plays a critical role in building this trust. Community-based participatory research that achieves a balance between research and action can help ensure that tribe-specific issues are addressed.

Recent research by the Housing Assistance Council and the Corporation for Supportive Housing leads to a number of recommendations that can help increase the accuracy of homeless counts – or broader housing needs assessments – on American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian lands.

-

Conduct outreach. Identify appropriate leaders and staff who can communicate the importance of collecting data on homelessness; describe the long-term benefits of the survey to the tribe; act as a liaison between tribal departments, councils, and outside partners; engage key stakeholders; and provide the overall leadership necessary to implement the survey. Keep both the tribal government and the larger tribal community informed and engaged throughout the process. -

Plan and implement the survey carefully. Develop a survey tool that is culturally appropriate while asking questions about housing and economic conditions. Consider whether to administer the survey door-to-door or at a community center, depending on what will work best for the tribe involved. Publicize the survey to increase understanding and encourage participation. -

Partner with researchers and intermediary organizations. For some tribes, partnering with intermediary organizations may be critical to help coordinate survey efforts, especially if many tribal bands are attempting to coordinate the effort across a large geographic area. Select an organization that has an existing relationship with the tribe, or take the time up-front to build rapport and trust between the organization and the tribal community. Make the organization aware of any negative tribal experiences with other survey and research efforts, so that it can take them into account. -

Fund the project. Raising the necessary funds can be one of the most challenging parts of conducting a survey. Develop a budget that includes costs related to survey tool development, interviewer training, interviewer labor, potential stipends for survey participants, data analysis, final report preparation, and printing, shipping, and dissemination of the report. Local philanthropic organizations and state housing and human development organizations may be possible funding sources, if the project is presented effectively. Finding research partners early in the process may help tribes access funding, as universities and research firms may have connections with federal research entities and research-focused foundations.

These recommendations are drawn from Conducting Homeless Counts on Native Lands: A Toolkit, forthcoming from the Housing Assistance Council and the Corporation for Supportive Housing.

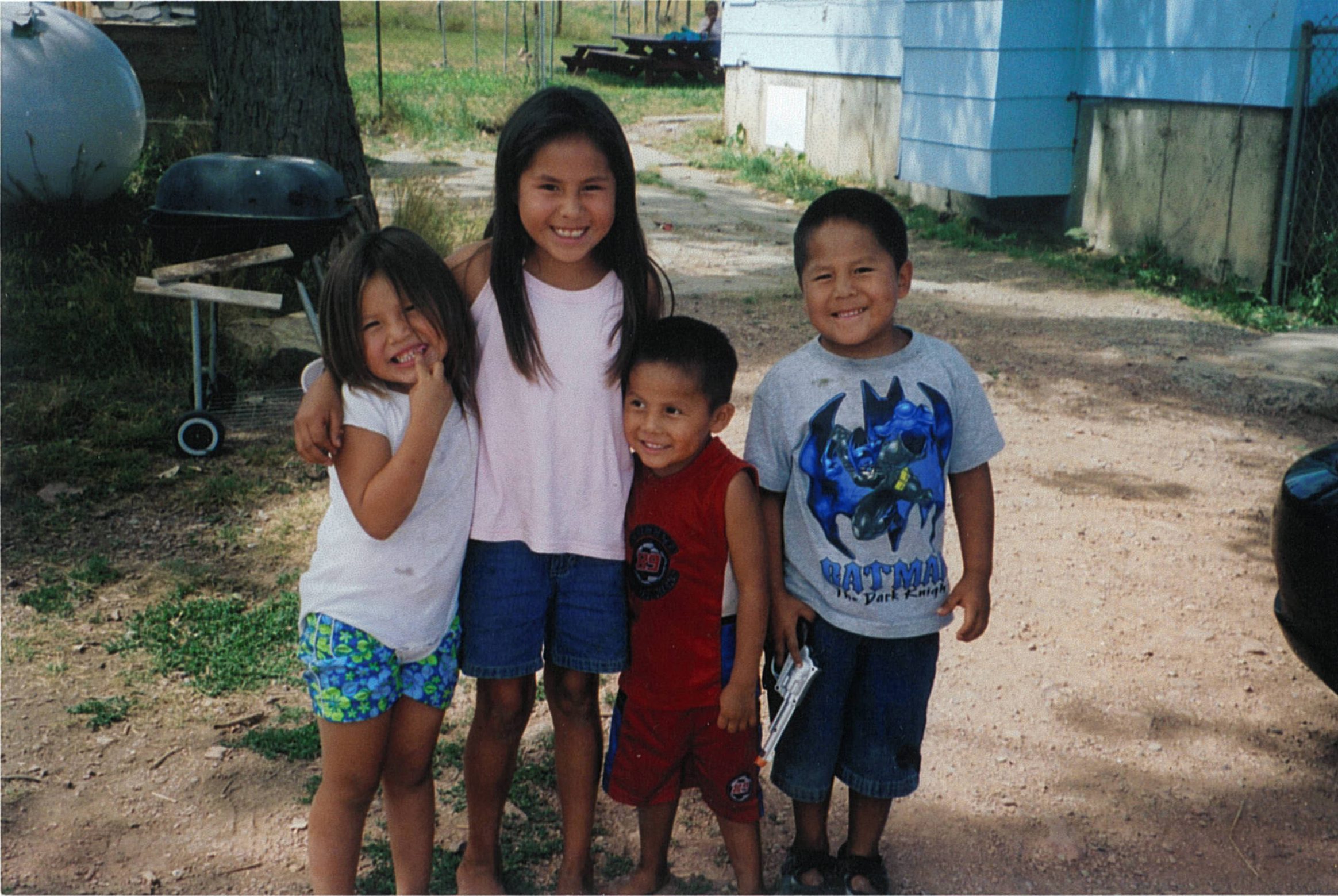

(Photo of children on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana by the Housing Assistance Council.)

Is the Bureau of Indian Affairs involved?

From what I know the BIA is only involved with the Housing Improvement Program (HIP). Applicants for the program must have housing that is substandard to receive funding. Furthermore, applicants must not have received any housing assistance after 10/1/86 for repairs, replacements, or down payment assistance. You must also not be living in a federally sponsored housing program so it really isn’t too wide reaching. So it another words, in order to get funding for the program you must first have a house. Although families that are way overcrowded could potentially add additional rooms to their house if they haven’t gotten any housing assistance in the last 26 years, the doubled up family or individuals would not be about to get their own home through the program. The BIA advertises this program as a “secondary, safety-net program” making it seem to me that this is more of a last resort if families are unable to find any other housing opportunities and have not been provided housing assistance for years.

That said, if tribes are looking to conduct homeless counts internally, the BIA could potentially provide an important role in outreach or finding potential partner organizations. It would depend upon the potential benefits tribal leaders or housing advocates determine could exist through their involvement.