Our anti-poverty policies have failed the suburban poor, say Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube.

Their new book, “Confronting Suburban Poverty in America,” highlights our country’s historically fragmented approach to urban poverty, and how that has limited the effectiveness of public policies and funding mechanisms. While the establishment of HUD as a cabinet-level office did much to unite the then-disparate programs that served to combat poverty, there remains considerable division throughout federal and state government.

This fragmentation is particularly telling when analyzing programs and funding mechanisms designed to combat poverty outside of urban areas.

The book also spurred a website dedicated to the same theme. The project is of superb depth, and one can find an enormous amount of data and policy recommendations on the site and through Brookings, which published the book.

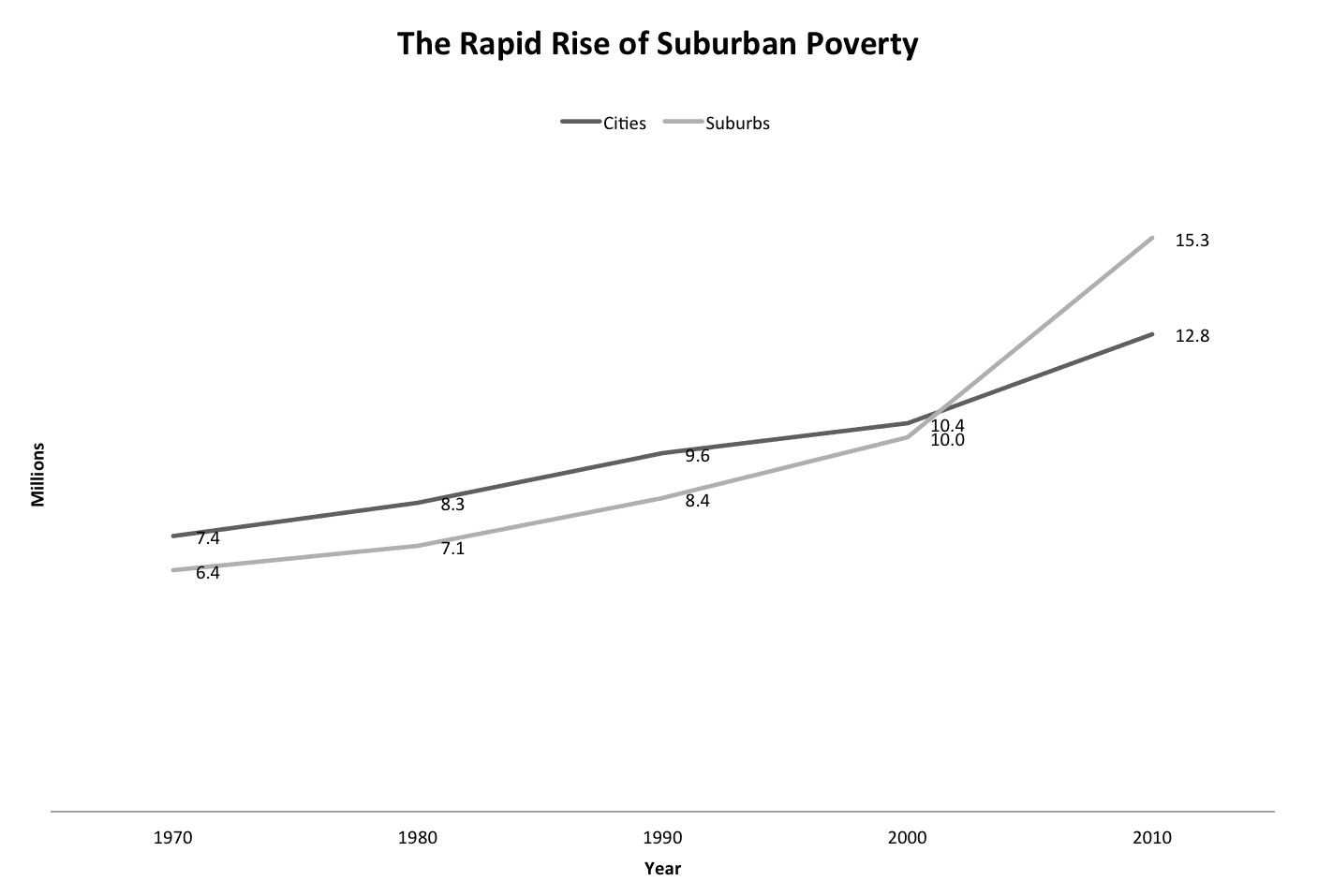

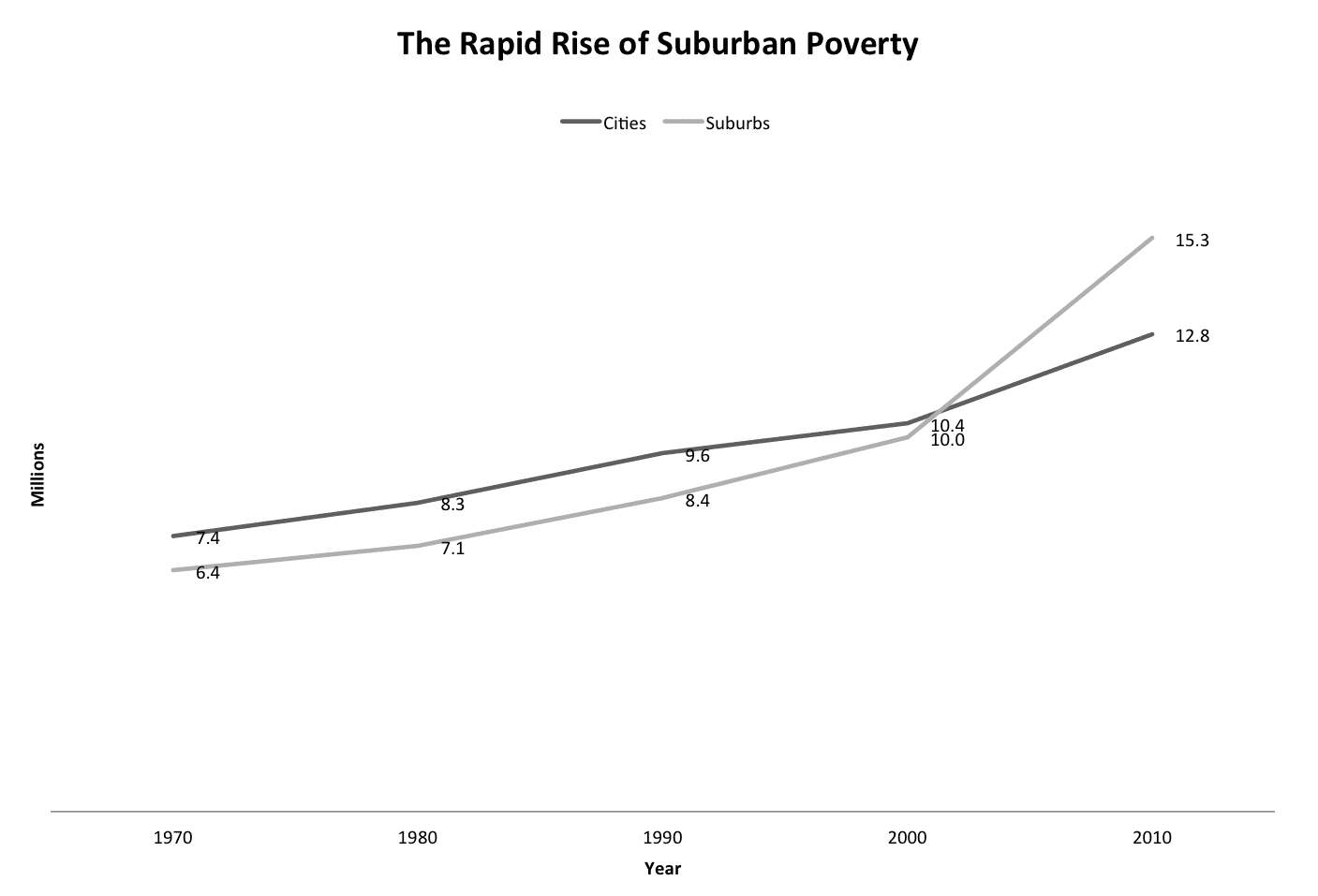

Increasingly, poverty in America is found in suburban communities, small towns, and rural areas. However, we continue to use policies and methods that were created and honed for use in cities. As Luis Ubiñas, president of the Ford Foundation, pointed out in the Brookings webcast marking the release of the book, non-urban poverty has many of the same challenges as urban poverty, but without much of the infrastructure present in cities.

There are many examples of how urban-centered policies are inadequate. Here are a few:

- Public transport primarily includes schedules that assume a commute into a city, not from suburb to suburb, enhancing car dependence, straining low-income suburban households;

- Key services such as child care, health care, and job training are seldom located in suburban areas, limiting access to needed resources;

- Section 8 vouchers to support housing mobility are of little use in the suburbs where rental housing is scarce and few landlords accept them;

- Stigma surrounding programs such as free school lunch, EFT, and housing subsidies may be felt more strongly in the suburbs where fewer people utilize these services. This may prevent households who qualify for such programs from taking advantage of them.

Another of the big issues that the research from Brookings brings forth is how we as Americans see poverty. Public opinion studies demonstrate that Americans consistently link “poverty” and “minority status” in our minds.

The emphasis in public policy and in the media on urban poverty (not to mention, the title of the cabinet office most dedicated to poverty) has enhanced these perceptions and stereotypes that are so unfortunately prevalent today.

Americans think of the poor as urban and non-white, and the perception that urban poverty is somehow unique contributes to the racialization of poverty in the media and in our minds. It is easy for white, middle-class Americans to view the poor as different, as “others,” if they are brown city-dwellers. Confronting the reality of suburban and rural poverty—of white, working-class poverty—may change perceptions and promote broader support for anti-poverty policies.

As Kneebone and Berube conclude:

“Rather than shift limited resources from poor urban to poor suburban communities, we need new policies and practices that confront barriers to opportunity not just at the community level, but at the regional scale of the economy. Almost 50 years after the War on Poverty began, we must renew the challenge and unleash new and adaptive systems that build and rebuild ladders of opportunity for poor families and communities nationwide.”

The Brookings project on suburban poverty makes important points about how poverty today is no less important than the urban poverty of the past, and that we need to address it using innovative, regional approaches.

However, by emphasizing suburban poverty alongside urban, they may be perpetuating a “geographic” emphasis of poverty that excludes rural areas. When looking at regional approaches to address poverty, we need to establish access and opportunity for all households: Urban, suburban, and rural.

I would suggest that broadening the understanding of non-urban poverty might serve to change our stereotypes of the poor, reduce the tendency to view the poor as a somehow lesser “other” population, and move forward with programs that truly enhance opportunity for the less fortunate everywhere.

Thank you for promoting inclusiveness and acknowledging the need to address rural poverty as well as urban and suburban!

The Brookings report provides a fairly powerful headline, but before we rush to judgement, a couple of things to consider.

First, Brookings defines “suburb” as any municipality with less than 100,000 people regardless of its wealth, density, housing character, or anything else. Wealthy communities with mostly single family homeownership can be considered “urban” and dense, poor cities with significant rental housing can be considered “suburbs” under the Brookings definition. Such a definition makes the use of the word “suburb” virtually meaningless, especially where I live in Boston where our metro region contains many dense cities with long standing poor populations that Brookings considers to be “suburbs.” There may in fact be more poor people in the “suburbs” but if we don’t have a shared understanding of what a “suburb” is than we might adopt the wrong policies.

Second, the notion that the Federal Government’s anti-poverty programs are too placed based is not correct. The largest anti-poverty programs in America are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid and these are not placed based. Brookings perpetuates the false impression that the Federal Government actually spends signficant money fighting poverty outside of these entitlement programs. With recent budget cuts, this is less true than ever.

Third, why does Brookings talk about a 50 year war on poverty? I think we gave up on that war in 1968 when the Vietnam War took our attention and money away. Pretending that we have been fighting a war on poverty for 50 years, when we have not been, dangerously reinforces the notion that federal programs are too expensive, don’t work and should be slashed.

Fourth, with a growing body of evidence connecting place to social/economic outcomes, I find it strange that Brookings is now recommending that we focus less on efforts to improve places. I thought we were all done with the tired debate about place-based vs. people based efforts and that we all agreed both were needed.

The Brookings report offers important and useful data, but let’s not jump to conclusions without a deeper understanding of the facts.

I don’t think this report is “recommending that we focus less on efforts to improve places” at all.

I also don’t think that the people vs place debate is even remotely over. While I personally agree that we need both, there is considerably policy debate regarding which should be prioritized and how.