Unfortunately, several generations later, the program is better known by its almost universal ineffectiveness than by the people it has lifted out of poverty. In Milwaukee last week, residents of the Westlawn complex and the faith advocacy group MICAH heard testimony about how the program has let down low-income Milwaukee job seekers and minority contractors.

It's an old, familiar story to MICAH. Due to the group's advocacy, on March 6 of this year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity conducted a review of the Westlawn complex and of the Milwaukee housing authority. MICAH and others are still waiting to hear the results of the investigation.

Section 3 is one of three important sets of workforce regulations: The minority hiring goals for federally-funded projects administered by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) at the Department of Labor (DOL); the apprenticeship regulations administered by the Education and Training Administration (ETA) at DOL; and the HUD Section 3 workforce regulations.

These regulations are some of the most powerful tools available to advocates and the government for ensuring that an equitable share of jobs on federally-funded projects goes to women and minorities andengaging in innovative approaches to apprenticeship programs that are critical to putting low-income people, people of color, and women onto a career pathway.

Unfortunately, they have been famously unenforced because of deficiencies in the language, significantly outdated data, and a failure to address the real world practices of the construction industry, including the existence of Project Labor Agreements (PLAs).

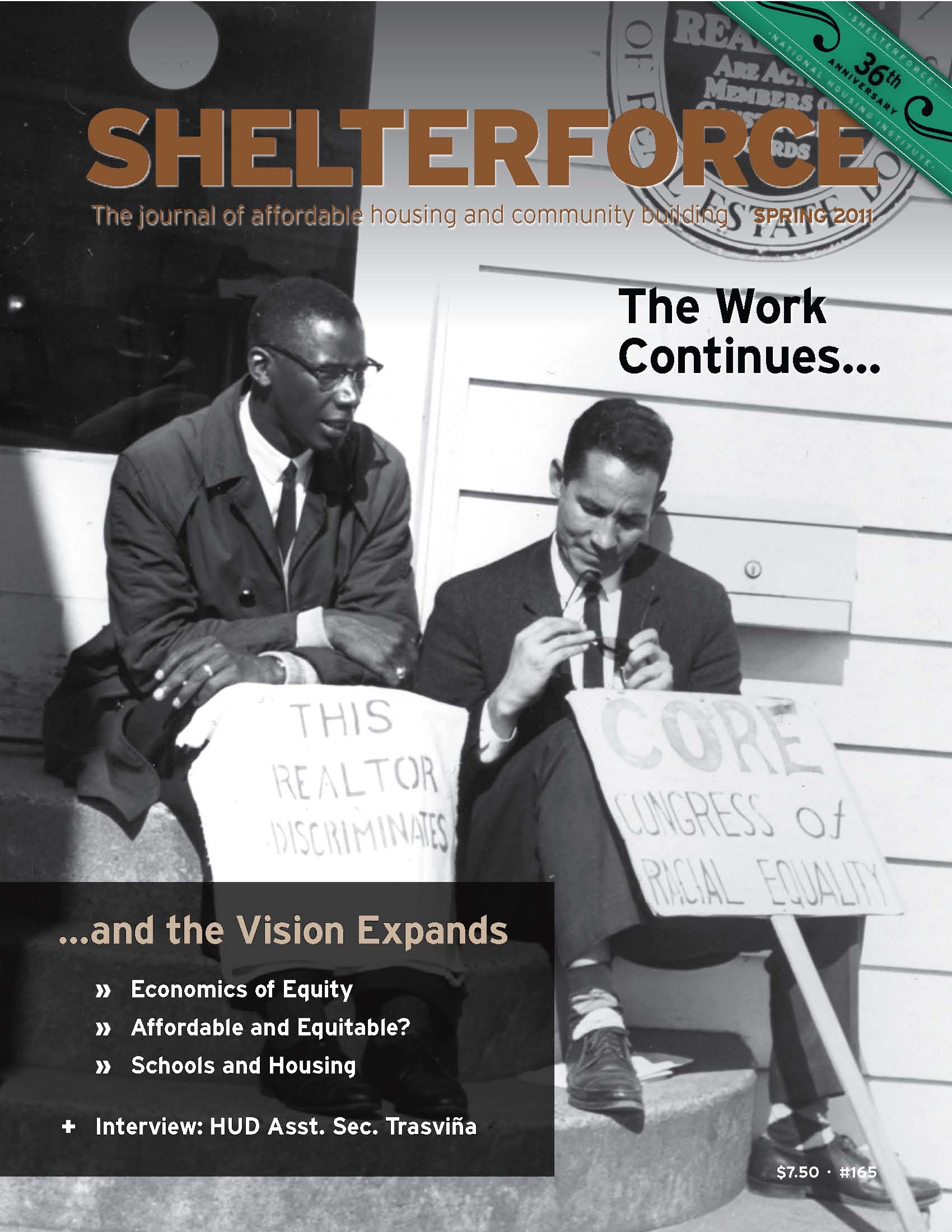

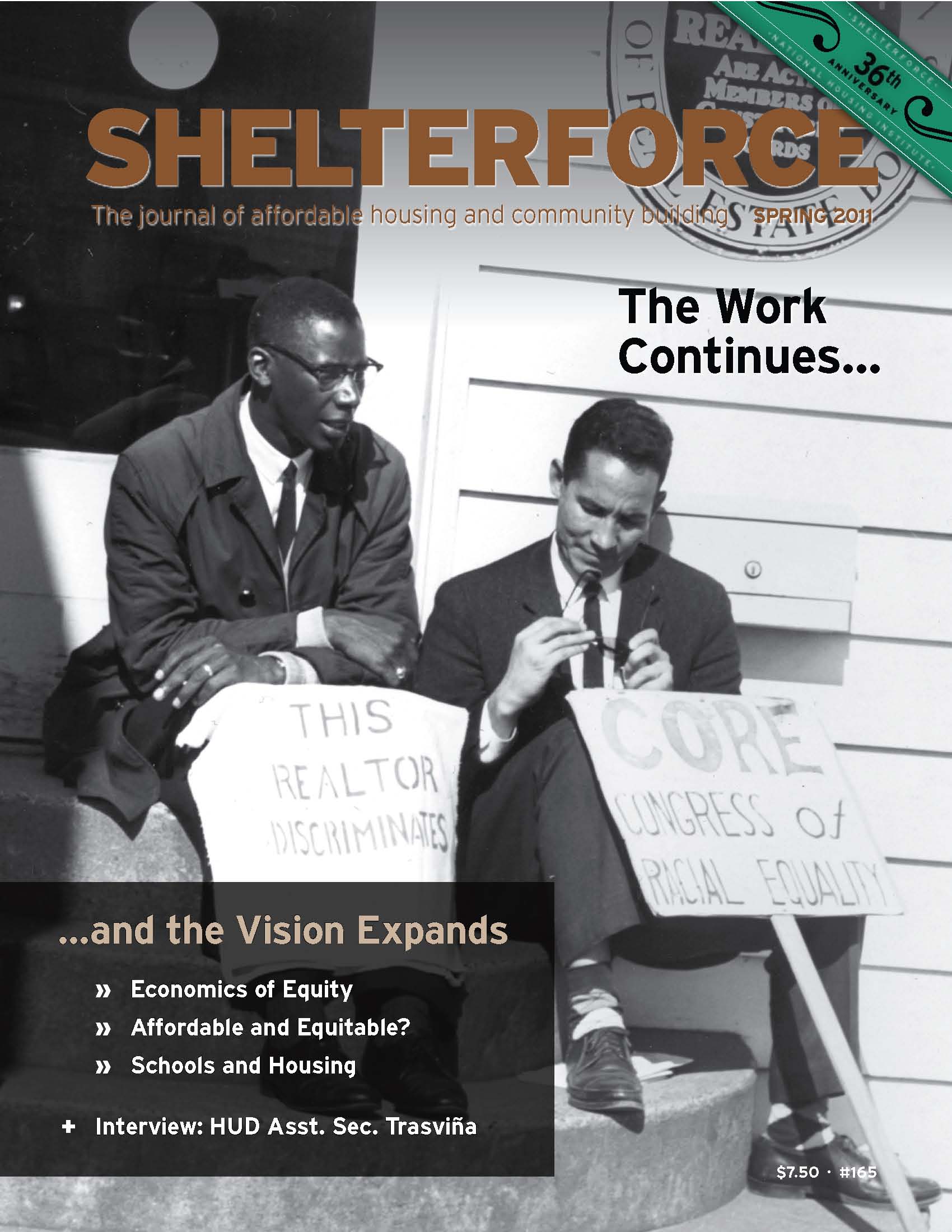

It's time now, in 2013, the year of the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, that these regulations need a second look. Revision of these regulations could move us closer to achieving our shared goal of equal employment opportunity for all.

Section 3 could be more than a good idea. It could be an engine of opportunity.

The ARRA funding is covered by Section 3 ..along with a line of other programs.Our President has the HUD sec3biz.gov registration on line to close the gap of opportunity.