Photos courtesy of Caley Vickerman

We hailed down a police car in Orange, N.J., and Police Director John Rappaport pulled over. We explained our situation. He thought for a moment. Then he was inspired.

“Oh fire hydrant,” Rappaport wrote next to a bright blue hydrant in pale pink sidewalk chalk. “Thank you for keeping us safe. In our homes and schools.”

I high fived a member of our team. We had just scored 10 points. During our day of participating in the Guerilla Haiku Scavenger Hunt, our group of chalkers ages 4 and up had written poetry next to a cherry tree, on a roof, and with a hot dog vendor.

Caley Vickerman, an actress and former math teacher, launched the Guerilla Haiku Movement in San Francisco in 2011. Last spring we hosted this street-based, poetry workshop in Orange as part of our annual placemaking events. Thirty of us split into teams and completed a haiku scavenger hunt with a point system. Haiku on a bridge? Two points. Haiku with someone in evening wear? Five points.

There were three guidelines:

Inspiration: Be inspired by what you see.

Celebration: Write haiku that celebrates what you see.

Engagement: Engage with people you see. Invite them to join you in writing haiku.

After our adventures we returned to ORNG Ink, a youth art and community center, to vote for the day’s best haiku. A group of card players taking a break from their Saturday afternoon game had the winning haiku:

Don’t sweat the small stuff

Be happy for small pleasures

Love like it’s OK

This summer Guerilla Haiku Movement landed in its 50th city. I met with Caley recently to talk about the movement.

“Urban spaces are comprised of people and communities. That is what we want to see and honor,” said Caley over coffee in Jersey City, her adopted hometown.

Caley learned haiku in her Grade 6 English class from Mrs. Williams and came upon the idea of writing haiku with strangers as a 20-something in a Boston bar to accomplish “allowing for encounters with strangers that are beautiful and meaningful and positive,” she said. She describes each haiku as a “word photograph.”

To celebrate the 50-city milestone I asked Caley to share some favorite images and anecdotes with Rooflines.

Caley had recently led Guerilla Haiku for students learning English as a second language at the New School. She said that the students at first thought approaching strangers on the street would be too hard, but they tried it and came back electrified. She shared this story in an email:

One of the students approached a man and asked him to write with them. The man was intrigued, and asked why—the students responded that they wanted to hear what he had to say. The man paused.

“I used to be a writer,” he said, “but I stopped because no one was reading my words.”

He picked up the offered chalk and scribbled this:

“A man lived here once

But they took his dignity

Now he is nothing“

The students were very touched by this moment and the man’s message.

Caley, who sometimes calls herself Haiku Mistress, shared another story:

A woman in Milwaukee, upon hearing the local NPR segment about Guerilla Haiku, brought her kids, ages 4 and 6, to participate. The kids were troupers, but a little young for full-days of haikuing. Caley was intrigued by the mom’s presence.

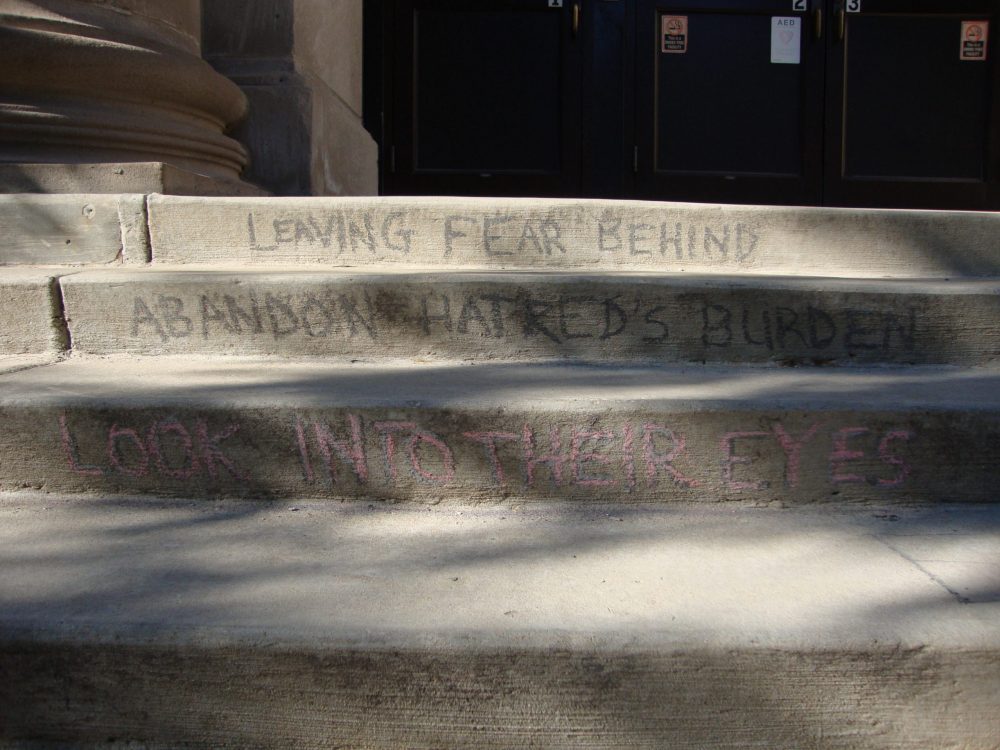

Curious, she joined their team and trailed them to their affluent neighborhood in Milwaukee. They chatted and chalked, and got other people to chalk. But the mom kept her cards pretty close. When the family made a bathroom run, she rifled through her clipboard, and found a pre-typed set of a dozen poems, written by the mom, all on the theme of tolerance. None of them had been written on streets that day, though.

“Why aren’t you using these?” Caley asked the woman.

She could come up with no suitable reason. They spent the rest of their time finding appropriate places for her words. On the steps to a school, in a playground, and on a busy street corner.

Comments