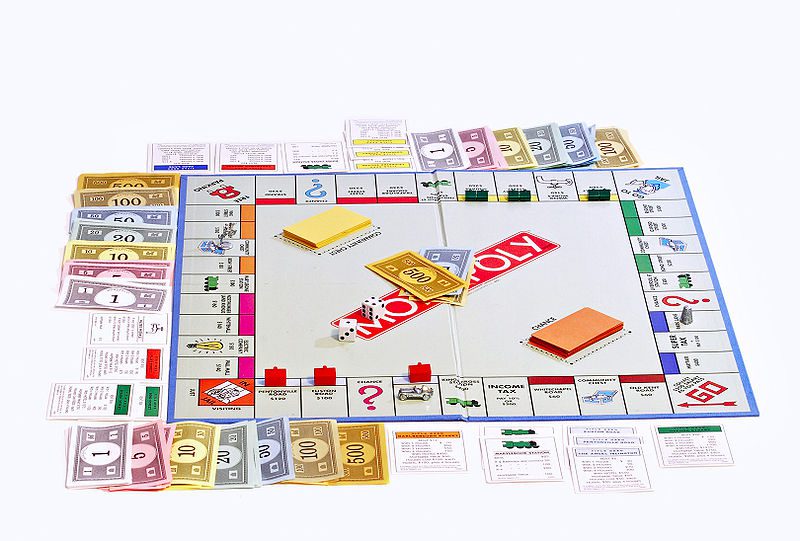

When I was a 20-something my family received a copy of the board game Monopoly as a gift. Being all varying levels of anti-capitalists, but certainly united in not being fans of rich guys in top hats and interminable games based on acting like tycoons, we were all quite satisfied with our decision to save the various game pieces for use with other games (especially those from the departed and sorely missed Cheap Ass Games, for which you always had to provide your own game pieces, dice, and counters) and toss the rest in the garbage.

Imagine my embarrassment to learn, at a recent conference on community land trusts, that Monopoly was first invented under the name The Landlord Game to illustrate the problematic effects of private land ownership and the system of rents. Elizabeth Magie, who created the game in 1902, was a follower of Henry George, the economist who proposed a single tax on land value, and was in his own time a wildly popular author and public figure. For many years it was primarily played by economics students and Quakers.

Seeing Monopoly as promoting its own winning conditions as a social good is kind of like using the term “ethnic cleansing” as a serious descriptor of genocidal practices. Whoops.

But it was a great reminder to check my assumptions—all the more so because it came after a long string of reminders that the exaltation of private land ownership, something we are often led to believe was the foundation of this country’s existence, was by no means as taken for granted earlier to this country’s founding as it is now.

We often hear the quotes on this topic attributed to Chief Seattle “How can you buy or sell the sky, the warmth of the land? The idea is strange to us. If we do not own the freshness of the air and the sparkle of the water, how can you buy them?” and “the Earth does not belong to man—man belongs to the Earth.” But they are almost always put forward, even by those quoting them approvingly, as a quaint, noble savage idea that was run roughshod over by folks who could run a civilization.

But that’s a modern lens that sells everyone a bit short. Take, for example, Thomas Paine, author of The Rights of Man: “Man did not make the earth, and though he had a natural right to occupy it, he had no right to locate his property in perpetuity in any part of it . . . It is the value of the improvement only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property” (Agrarian Justice, 1797)

And Abraham Lincoln: “The land, the earth God gave man for his home, sustenance, and support, should never be the possession of any man, corporation, society, or unfriendly government, any more than the air or water.”

And Henry George: “What is more preposterous than the treatment of land as individual property? In every essential, land differs from those things which, being the product of human labor, are rightfully property” (The First Great Reform, 1883).

Head spinning yet?

I learned all this in a session on the intellectual and historical roots of the community land trust, a form of organization in which a stewarding organization holds land in trust and sells (or rents) the homes on it, with resale restrictions so they stay affordable in perpetuity. (See a version of the presentation here.)

I’m a big fan of community land trusts, but the bigger point I took away was yet another reminder that the things that today’s conventional wisdom tell us have always been so and must always be so about how we organize our economy are not necessarily any more true than claims about how marriage has always meant what the religious right thinks it means now, or that pink and blue are naturally more appealing to certain genders (in fact 100 years ago the genders associated with these colors were reversed).

Sometimes I think those of us who want to question some very fundamental things about how our culture does things fall into the trap of thinking we’re the first ones to be considering questioning them, or at least the first in anything like our context and culture. It can make any radical change feel rather more impossible than it necessarily is.

So if you are an activist feeling in need of perspective, maybe go seek out some history that kicks your assumptions in the head. And if you can stand it (I still can’t), maybe play a little Monopoly, in the spirit it was originally intended.

Comments