We know that new manufactured homes cost half of what site-built homes cost (absent land). We also know that manufactured home mortgages can perform as well as other mortgages, especially if done responsibly. But for a homeowner to get these benefits, he or she has to be able to find a home for their home. That is, their jurisdiction can’t be one of the 40 percent or so that restrict manufactured homes to special zones or to “parks.” It also is too burdensome to live in one of the 20 percent of communities that requires a special permit to site a manufactured home in a typical single-family zone. Clearly, if communities are serious about affordable housing, they need to add manufactured homes to their toolkit.

Many of these restrictions have roots in the low quality that was far too prevalent prior to the enactment of the so-called HUD code in 1976. This code, many readers know, standardized quality and drove the industry to innovation and better products. What also followed has been better design, so much so that many models of today’s manufactured homes are indistinguishable from site-built homes built in suburban subdivisions or as urban infill.

So what should advocates and policymakers do? To be blunt, the most effective way is to advocate for state statutory changes. Specifically, states need to do what Washington did in 2004 and what California did decades earlier: prevent localities from prohibiting manufactured housing in single-family neighborhoods.

About half the states address manufactured housing and local zoning in some way, but they vary tremendously, and may simply require that a locality allow manufactured homes somewhere, anywhere within its borders. (NCLC—the source of this data—and CFED are working to update the linked resource.)

This not a new issue; since California first began to address the discrimination against these homes in 1980, various housing experts have opined against the unfair treatment. Yet many of these criticisms had less poignancy then than they do now. Before 1980, most housing programs were reasonably well funded, and believe it or not, Members of Congress from both parties recognized the value of providing housing assistance in various ways to families priced out of the market.

It may be heresy to remind some, but the last truly meaningful housing program launched, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, was adopted by a Republican Senate and signed into law by President Reagan. (We don’t need to debate the credit’s significance in the huge Tax Reform Act of 1986, but LIHTC was adopted in a bipartisan way.) While LIHTC did not make up for the huge cuts to Public Housing and other programs, it at least indicated that housing programs were at one time doable.

No longer.

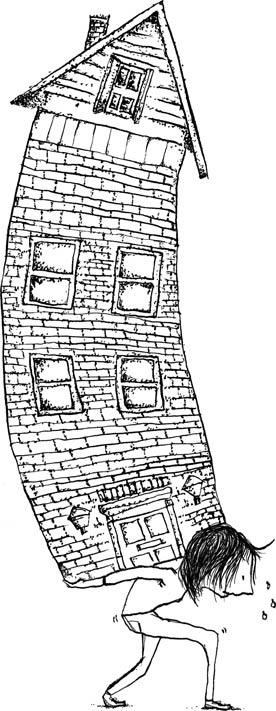

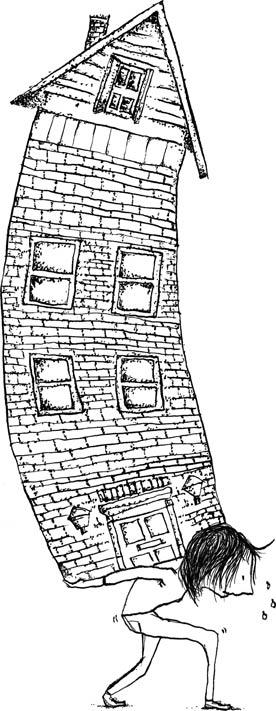

There is still a housing crisis across the country. And there is no will in Congress, particularly in the House, to address it seriously. So the burden falls to the states and localities to do so. But housing programs can be very costly, so many states have shied away from meaningful programs. (As an example, while 47 states, and DC, have housing trust funds, which are widely acknowledged to be an effective way to fund housing and leverage public and private resources, 20 fail to fund them.)

Knowing all this, which policymakers and housing advocates do, it is a no-brainer to use a housing type that can blend in with existing stock and cost half as much as other options. But too many localities, as noted above, block its use. Just in recent weeks, Pratt, Kansas, banned manufactured housing in certain zones and homeowners in Lewes, Delaware, face a local law that prevents them from updating or replacing their manufactured homes. Pratt city leaders did this even as local news reports that traditional construction costs and market conditions worsen the local affordable housing shortage.

The New York State legislature stepped up and its members promoted a bill that would require “the equal application of local land-use controls and appearance criteria to both manufactured housing and site-built housing.” Sadly, however, opposition from trade organizations, using language reminiscent of the misinformation we often hear from home builders, may have killed the bill, which they say would subject localities to homes shipped from “across the country or the world.”

This bill could be a huge help as cities look to do infill, suburbs explore low-cost and mixed income subdivisions, and rural advocates discover that manufactured homes are not trailers and certainly not mobile. We hope the state assembly moves beyond the self-interested opposition to pass this legislation.

I’M HOME has great partners in New York and there is a great need for new thinking on affordable housing. While treating manufactured homes like site-built homes won’t solve the affordable housing crisis, failing to do so demonstrates, quite simply, a lack of seriousness on the issue.

As our partner, Next Step, says, “A home is a home. It’s that simple.”

Comments