Nine years on, New Orleans is a very different place from what it was like in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. What may be more notable, though, as I came away from a recent visit thinking, is that it is also in the process of becoming a very different place from the pre-Katrina city. New Orleans today is a fascinating case of a city in evolution, where it is still unclear what it will evolve into over the coming years. It is now pretty clear that a large percentage of those who left New Orleans after Katrina and have not come back yet, are unlikely to come back.

The city’s population today is about 100,000 below its 2000 population. Growth, while steady, has slowed down since 2010, by which point most people had returned. By all accounts, the people moving into New Orleans today—for a net increase of about 9,000 per year according to the Census—are coming from all over, moving to the city for the same reasons that people move anywhere else, because they want to be there.

New Orleans today is a city with fewer families, a lot fewer children, and a lot more single people—while the total number of households is down 19 percent from 2000, the number of households with children is down 42 percent. Not only are fewer new families with children moving in, but among those who left after Katrina, it looks like far fewer families with children came back. New Orleans is a much whiter city today. Fewer white than black residents left after Katrina, reflecting the greater impact the hurricane had on largely black neighborhoods. New arrivals, heavily skewed to young, college-educated adults, are far more likely to be white than black. Although non-Latino whites make up only about one-third of the city’s population, two-thirds of the new arrivals between 2011 and 2012 were white.

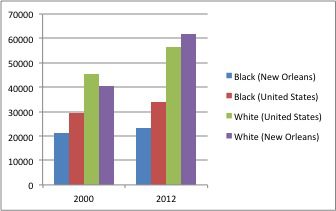

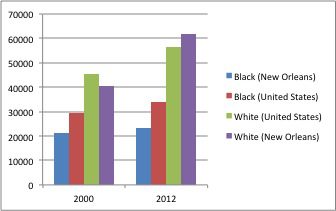

Contrary to some impressions, the city’s Latino population is still relatively small; Latinos make up 5 percent of New Orleans’ population today, compared to 3 percent before Katrina. New Orleans is also an unequal city, in which white households are not only far more affluent on the average than black households, but where the gap has grown dramatically over the past decade. In 2000, the median black household earned 53 percent what the median white household earned—already a larger gap than the national black/white income gap—but by 2012, the median black household was only earning 38 percent what the median white household was making. While white households earned 10 percent less than the national white median in 2000, today their income is 10 percent greater than nationally.

New Orleans before Katrina was a rarity among major American cities, a city where almost everyone was “from here,” where people tended to be rooted in their neighborhoods, and where neighborhood traditions and customs were far more intensely cultivated than in most American cities.

A saying on a T-shirt I saw in a store window in the French Quarter, attributed to Tennessee Williams, sums it up—“the United States has only three cities: New York, San Francisco and New Orleans. Everything else is Cleveland.”

For all the Mardi Gras floats and beignets, though, New Orleans was also a poor, steadily declining city, which had lost over 150,000 people over the decades before Katrina hit, and where—and many people forget this—vacant lots, and abandoned boarded houses, were endemic, more so than almost any other American city. As one long-time resident told me, “we were just slowly sinking into the sunset.”

New Orleans is no longer declining, but the way it is changing is deeply unsettling to a lot of long-time residents. More and more of the people on the streets and in the workplaces are no longer “from here.” Rents have skyrocketed, rising over 50 percent in the first couple of years after Katrina. While house prices in most parts of the city are still relatively modest, burdensome flood insurance costs make homeownership much less affordable than meets the eye. The g word—gentrification—is heard more and more often, as people try to make sense of an environment that is shifting under their feet. It is likely that some gentrification—in the sense of accelerated racial and economic change at the neighborhood level—is taking place, but it’s hard to pin down how much. New Orleans has become a much more expensive city than it was, but a lot of that is for other reasons.

One big factor in the higher rental prices is the fact that at a time when demand has skyrocketed, a host of legal and financial issues have made it incredibly difficult to create more rental housing, either affordable or more expensive housing – a shocking anomaly in a city where vacant houses and lots are all but omnipresent. To the city’s credit, they are actively exploring ways to break the logjam. The big takeaway, though, is that New Orleans’ most pressing problems today are no longer about post-disaster reconstruction, but the problems of a “normal” city.

While reconstruction continues, and will probably continue for decades, and while the threat of another hurricane is always in the back of people’s minds, these are no longer the issues that will chart the future of New Orleans as a city. New Orleans now has to deal with changing economic conditions, changing demographic realities, and—as is true of other American cities—growing social, economic and racial inequality. The questions are first, whether the city can successfully manage the changes taking place; and second, whether it can do so in a way that will enable it to retain not only its distinctive buildings, but its distinctive social fabric and traditions. Or will it turn out to be Cleveland?

Perhaps taking cues from T-shirts in the French Quarter to make broad-brushed generalizations, may not be the best thing for article credibility, or maybe having a less than 30 minute commute, an affordable cost of living, access to plentiful fresh water and an incredible park system are bad things??

Visit Cleveland, Mr. Mallach, and we will get you a cool t-shirt for your next article.

When I was growing up, my immigrant father had a saying, “bei uns in Shnipitschok”, which he would use to describe things he considered quaintly old-world, but basically out of it. I assumed he’d made up the name, but it turned out, as I learned later, that there really was a town called Shnipitschok, just across the river from Vilna (it’s still there, and now called Snipiskes). I’m quite sure my father had never been there, but just liked the sound of it. My point is that sometimes a place is a place, and sometimes it’s a metaphor, and that it is not worth people’s while to get upset about it. As a long-time resident of New Jersey, another place that is often used as a metaphor by people, I’m used to it.

Just for the record, I know Cleveland well, have visited it often, have many friends there, and have worked with its officials and community leaders to help address many of its challenges. It also has one of the country’s finest park systems, and fabulous architecture. And the Cleveland Clinic. And, also for the record, I didn’t buy the t-shirt.

And sometimes a metaphor takes away from all that work you, and many others have done, and continue to do, to help address many of its challenges.

I’m glad you didn’t buy it, Mr. Mallach, but if you send me your size preference, I’ll get you an NHS of Greater Cleveland tshirt.

Actually it sounds like New Orleans is remaining quite the same place it has always been, in a sense. It has always been full of transients. It has always periodically flushed people out, and replaced them with new people.

I think the fear that new residents will change the city is as silly as the fear that Germans would change it. New Orleans will always be New Orleans.