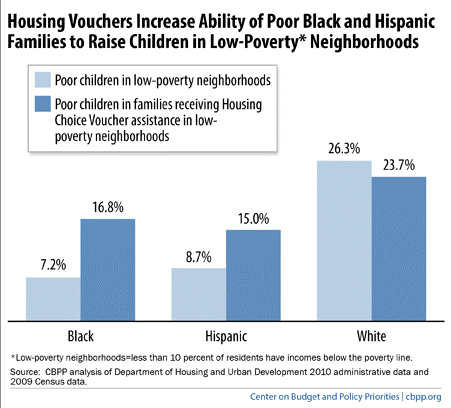

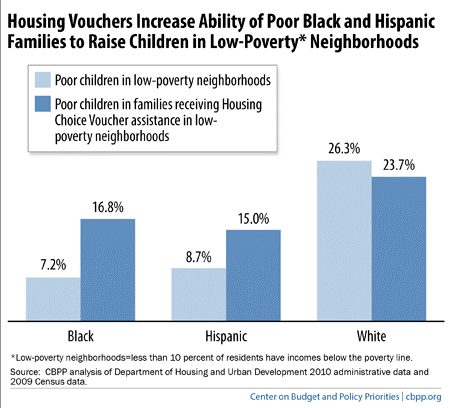

Among poor families, more than twice the share of black children and close to twice the share of Hispanic children using housing vouchers lived in low-poverty neighborhoods (those with less than 10 percent poverty) in 2010, compared with poor black and Hispanic children generally (see chart). In contrast, poor white children in families with vouchers were slightly less likely to live in low-poverty neighborhoods than poor white children overall.

For families of color, using a voucher to rent housing also slightly improves the schools that their children are likely to attend, compared with their poor counterparts. The median school nearest to both black and Hispanic voucher holders ranked higher on math and reading tests than the median school nearest to poor black and Hispanic households generally.

Housing vouchers also help poor black and Hispanic families with children avoid neighborhoods of concentrated poverty [Editors note: earlier Rooflines posts have argued that this is not the case. See examples here and here.] Researchers generally agree that living in neighborhoods of extreme poverty, in which 40 percent or more of the inhabitants are poor, is particularly harmful to children because they are more likely than others to have higher rates of crime and violence, poorly performing schools, fewer college-educated adults, low employment rates, and limited opportunities for physical exercise.

Poor black and Hispanic children are more than five times as likely to live in a neighborhood where 40 percent or more of the residents are poor than poor non-Hispanic white children. Living in an extremely poor neighborhood may be particularly harmful for children when families live in such neighborhoods for several generations, which occurs at a greater rate among African-American families.

But housing vouchers improve these statistics substantially for poor black and Hispanic families with children. For these families, vouchers cut their likelihood of living in extreme-poverty neighborhoods by nearly half for black children and more than a third for Hispanic children, compared with poor children of the same race or ethnicity.

While these are encouraging statistics, the Housing Choice Voucher program can do more to deliver on its potential to help families avoid living in neighborhoods likely to hurt children’s economic prospects and future health, as summarized in a recent blog.

Comments