An answer can be found close by in Puerto Rico, where the communities of the World Habitat award-winning Caño Martín Peña project have succeeded in building community power and gaining control of their land by pioneering the first application of the community land trust model to an informally owned settlement. To accomplish this feat, the people who live on the settlement have developed strong community roots and political clout, leading to the establishment of several new local institutions, a broad network of support both within Puerto Rico and globally, and an impressive string of political victories. But such successes have not occurred overnight, nor are they the result of technical solutions imposed from above by experts—they are the result of over 15 years of deep community organizing and empowerment.

In February, I visited Caño Martín Peña with a dozen housing and community advocates from Europe and the Americas as part of a peer-housing exchange organized by BSFH, the British NGO that awards the World Habitat prize each year. About 26,000 people live in the eight communities surrounding the Martín Peña Channel, a highly polluted waterway running through central San Juan. Many are informal settlements along the river or on infill within its former boundaries. Decades of trash and government-promoted infill has reduced the channel from a navigable waterway to a stagnant, impassible trickle. The channel floods frequently, and because thousands of homes in the area lack sewer systems, with flooding comes widespread exposure to raw sewage and its related health and safety consequences.

Adopting the Community Land Trust Model to Prevent Displacement

To ensure their voice would be present in the future development of the channel, community members developed a comprehensive plan to clean up the waterway and avoid displacement. After much deliberation, the community decided that a land trust structure would best meet their needs, since it would allow families to formalize their properties through the granting of surface rights and placing land under community control. Community ownership of land through the trust will ensure that home prices remain affordable and that land use decisions benefit the community as a whole, while avoiding a speculative real estate market that could lead to displacement. The plan also provides for the relocation of the homes located in the most flood-prone and unsafe areas as well as infrastructure improvements, including comprehensive sewage coverage.

From Engagement to Empowerment

The scale of the engagement process demonstrates a genuine, deliberate commitment on the part of project organizers to move well beyond community consultation for input into the future of the channel, to active community organizing and empowerment, ensuring community participation in both envisioning a plan for its future and steering it.

To create the community development and land use plan, residents knocked on every door in the eight communities surrounding the channel and conducted an astounding 700-plus meetings, workshops, and related events over three years. Knowing that not all community members would prefer or be able to attend so many meetings, they also created an informal democratic system where each street selected representatives to serve as point-persons for the participatory process.

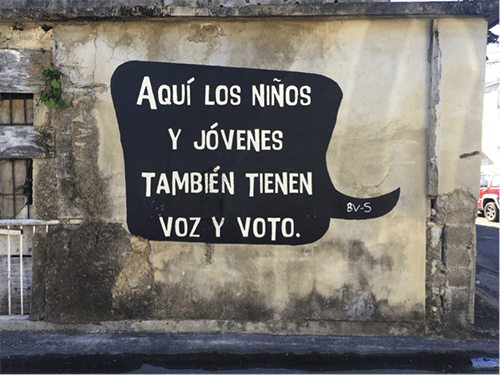

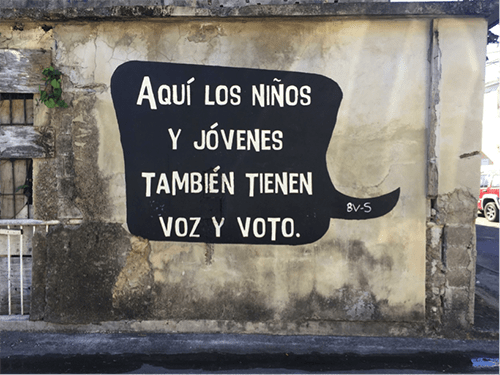

Today, the community land trust’s structure reflects this commitment to community participation, with its members forming an assembly that has decision-making powers. In addition to creating the land trust, the planning process also fostered the creation of several new initiatives to increase civic participation and better meet resident needs. This includes two new organizations, ENLACE, a public-private agency tasked with implementing the community development and land use plan, and G-8, which serves as a coordinating arm and dispute resolution mechanism among the eight communities lining the channel. Like the land trust, G-8 has its own resident assembly to make decisions, as most members of the eight communities live outside of the land trust borders. The trust has also launched a robust youth leadership program, ecotourism start-ups, urban farms, and adult literacy classes, among others.

Taken together, the effect is one of a social movement rather than a collection of institutions. Community members often appear in T-shirts with the slogan “Caño Martín Peña En La Lucha” (“Martin Peña Channel in the Fight”). In this case, “La Lucha” refers to many things: the fight for affordable housing and against displacement, the fight to clean up the channel, the fight for food sovereignty on an island where 85 percent of food is imported, the fight for youth participation in civic life, and more.

When Empowered Communities Fight . . . and Win

The community power behind the land trust was put to the test quickly: In May of 2009, the land was transferred from the Puerto Rican government to the Caño Martín Peña land trust. About a month later, the government took it back, passing a new law that reverted land ownership to the public domain. The ruling party, which had not been in power when the efforts to create the land trust were undertaken, justified this measure by arguing that giving individual land titles to residents would be preferable to having land under community ownership through the trust. However, others argued that the move reflected discomfort with the community power amassed through the land trust project, and the belief that a system of individual titles would make it easier to undertake major tourism redevelopment projects once the channel was cleaned up.

Efforts to override the government’s move in court failed: the First Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals found that the seizure was a legal public taking of land. With no further legal recourse, and knowing that the Puerto Rican government would be unable to provide the fair compensation for the land required by the Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution, the community decided to wait out the administration and began organizing around the 2012 elections. Community members appeared on every television and radio station in Puerto Rico, gained the support of major unions, took to the streets, and educated 2012 political candidates about their struggle.

As it turns out, a well-organized community of thousands of people can be extremely effective in influencing electoral politics: by the 2012 election, the Caño Martín Peña community succeeded in convincing every single mayoral and gubernatorial candidate to sign on to a pledge that they would restore the land back to the trust. The promise was kept, and the land was restored to the trust in 2013.

La Lucha Sigue

Of course, regaining control of the land is only one of many monumental tasks ahead for the Caño Martín Peña community. Today, the work of formalizing titles, relocating families from flood-prone homes, and installing sewage infrastructure continues. The channel has still not been dredged, and the Puerto Rican debt crisis and the resulting severe austerity regime imposed by the U.S. federal government will make progress in this area difficult if not impossible. In the wake of the crisis, investors and speculators are arriving to size up opportunities for profit, while record numbers of Puerto Ricans are leaving for the U.S..

Despite regaining its land, the Caño Martín Peña is not immune to the political and economic pressures caused by the debt crisis, though the international recognition it is currently receiving is helpful. Those in the U.S. can help by showing solidarity with Puerto Ricans as they face off against the federally created Financial Oversight Board and by demanding action from our elected officials.

At the same time, we can also take lessons learned from the Caño to heart. The project and its successes are a testament to the power of a community to determine its own course. It speaks to the benefits of investing in deep community organizing in the long term, rather than as part of a short-term project for which community engagement is a box to check. Like the Caño community, who are united “en la lucha,” working to promote connected and ambitious causes, we too can think bigger and set wide-ranging goals for our communities. We too can set the agenda and demand that our elected officials follow. And we too can invest in community organizing, coalition-building, and ongoing advocacy to ensure that we bring more people along with us and meet our housing and community development needs. With the Caño Martín Peña, we have an excellent example to follow.

Images: Courtesy of author

Comments