So Brendan Crain, of Project for Public Spaces (PPS), writes in his article “Get Out of the Way“ in the latest issue of Shelterforce. Crain describes some of PPS’s principles and approaches for getting people engaged in feeling ownership of public spaces and helping to make them more vibrant.

His comment about Kibera, which is a large slum area in Nairobi, Kenya, where PPS is working on a project to develop an athletic field, reminded me of something Richard Layman wrote here on Rooflines last year. Discussing some of the planning implications of more extended households living together post housing and financial bust, he wrote:

“As households become larger, more people will spend more time out-of-the-home on social activities, ‘to get away’ from the house and the cramped quarters. Parks and other public places, recreation spaces, active streets in commercial districts, and other places may become increasingly in demand as households become larger and multi-generational. Too often, community land use practices haven’t caught up to these changing circumstances as more people live in city centers.”

Layman notes that the same principle applies to on-site gathering spaces:

“Increasingly, higher end properties are providing high quality on-site amenities ranging from business centers, wi-fi, television projection rooms, outdoor kitchens and patios, fitness facilities, etc. From the standpoint of addressing ‘social exclusion’ through the provision of high quality programs and practices of ‘social inclusion,’ we need to ensure that social housing developments have high quality on-site amenities also.”

This rings true to me. More people in the city I live in now look for places to gather other than their own homes than it seems like was the default in the suburb in which I grew up (and that was a fairly dense streetcar suburb itself).

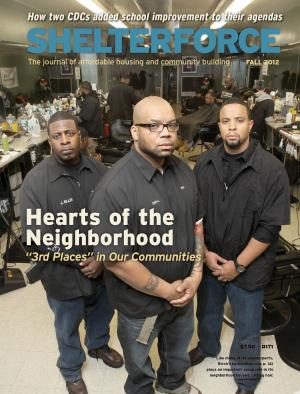

Ken Reardon opened up our third places roundtable with a related thought, not so much in terms of the density of low-income areas, but in terms of the loss of many standard community facilities in them, and the need for collective action in them:

“There are fewer community facilities, there are school closings, a lot of the neighborhood-oriented retail spaces are much less vibrant. So these remaining community spaces, whether they’re barbershops or a low-cost breakfast restaurant, are among the few gathering spaces that remain. And given the difficulties that these neighborhoods face, having civic conversation about critical policy issues becomes more important. So I think they’ve become more vital in many ways.”

So what do you think? Are third places not merely a question of parity or revitalizing areas, but actually more important in the communities where we work than in more affluent places?

Comments